|

| John Wesley |

Religious revival

Although the eighteenth century is seen as the Age of Reason, it also witnessed a profound religious revival that encompassed parts of central Europe, the British Isles and North America. New religious groups, most notably the Moravians sprang up to meet needs that the more established churches, whether Anglican or Dissenting, seemed inadequate to deal with. The Methodists

The first prominent Methodist was not John Wesley but George Whitefield, (1714-70), who was converted three years before Wesley and who at the time of Wesley's conversion was already using open-air preaching to dramatic effect. John Wesley (1703-91) entered Christ Church, Oxford in 1720. He and graduated in 1724. In 1728 he was ordained priest. In 1729 he returned to Oxford to fulfil the residential requirements of his fellowship. There he joined his brother Charles and others in a religious study group, the ‘Holy Club’, one of a number of societies of devout young men. These societies were concerned with the ‘reformation of manners’ – attacking swearing, blasphemy and Sabbath-breaking. The ordered lifestyle of the Oxford club earned them the nickname ‘Methodists’.Following his father’s death in 1735 Wesley sailed to the new American colony of Georgia to oversee the spiritual lives of the colonists and to do missionary work among the Indians as an agent for the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. On the voyage out there, the ship ran into a storm, and he and Charles were impressed and put to shame by the piety and courage of their Moravians fellow-voyagers, who, alone among the passengers showed no fear.

Wesley's time in Georgia was an unhappy one, and in December 1737 he virtually fled the colony, an unhappy and disappointed man.

Back in London he met a Moravian, Peter Böhler, who convinced him that what he needed was simply faith. On 24 May 1738, he attended a Moravian mission in Aldersgate - an experience that was a turning point for him. Following his conversion he embarked on a lifetime’s mission throughout the British Isles in which he travelled over 200,000 miles and preached over 40,000 sermons. He quickly found that the ancient parochial structure of England was inadequate to his purpose and was not adapted to new population movements.

In 1739 he was invited by George Whitefield to come to Bristol and help preach to the colliers at Kingswood Chase. He came and found himself, much against his will, preaching in the open air. This enterprise was the beginning of the Methodist revival. Wesley was astonished at the dramatic results that followed, and the mass emotion of the crowds. Soon he was building up ‘societies’ which took the Oxford nickname, ‘Methodists’. The Methodist society started at the Old Foundery, Moorfields, London and quickly spread to Bristol.

|

| The first Methodist chapel, the Old Foundery National Library of Wales |

|

| The New Room, Bristol (1739) The oldest surviving Methodist church Public Domain |

As the new buildings went up, the Methodists became institutionalised, though they were still part of the Church of England. Wesley always declared that the Methodists were a ‘society’ or a ‘connexion’ not a church. By 1771 Methodists numbered just over 26,000; by the time of Wesley's death in 1791 they were nearly 57,000.

Hostility

In spite of - perhaps because of - their success, the Methodists aroused extraordinary hostility. In 1748, for example, Wesley received a physical battering at Calne when the local curate advertised for volunteers to attack him. The war waged on the Staffordshire Methodists in 1743 and 1744 was perhaps the most bitter of all such campaigns of intimidation. |

| An idealised Victorian representation of Wesley preaching |

|

| Another Victorian representation: Wesley calmly confronts the crowds at Wednesbury |

They were unpopular because they were ‘irregular’. They conducted mass meetings, they 'poached' Church of England territory, they had (in their early days) women preachers like Mary Bosanquet. They were constantly accused of superstition, credulity, extravagant behaviour.

A separate denomination

Methodists in America found their work seriously affected when war broke out, and with the withdrawal of many Anglican clergy there was no-one to whom his followers could go to receive Communion. Accordingly in 1784, when the independence of the United States was confirmed, Wesley took a stand on his right as a priest of the Church of England to ordain men on his own initiative. This was a dramatic break with Anglican practice. In 1784 he drew up a Deed of Declaration; this appointed a Conference of 100 men (the ‘Legal Hundred’) to govern the Church after his death. In effect, the Methodists were now a separate denomination.

Anglican Evangelicals

The awakening was wider than Methodism and included prominent clergy who remained in their parishes and never adopted Methodist itinerancy. One of the most celebrated of these was John Newton, now best known as the author of the hymn, 'Amazing Grace'. He was instrumental in the conversion of the young William Wilberforce in 1785.The 1780s were a key decade in the history of the Evangelical movement, when they took up the cause of the abolition of the slave trade. One of the most remarkable campaigners for this cause was the former slave, Olaudah Equiano, formerly known as Gustavus Vasa. Both Newton and Equiano wrote remarkable autobiographies, which were classics of the narrative of the spiritual journey and contained many details about the slave trade.

John Newton

|

| John Newton |

Newton published his spiritual autobiography, the Authentic Life in 1764. It is a story of press-ganging, flogging, near-death from fever and then drowning, blaspheming, slave-trading, and then ordination into the Anglican priesthood. It is also a love story of how, after many years of separation, he was able to marry his childhood sweetheart.

Slave trader

He was born in Wapping in 1725, the son of a captain of merchant ships. He never received a formal education but began his seafaring career at the age of eleven. After a storm at sea in 1748 he became a devout Christian - but with a terrible blind spot. In the summer of the same year he became first mate on the Liverpool slave ship, the Brownlow, one of the 322 ships in the 1740s that sailed from Liverpool to West Africa and then shipped 78, 890 Africans to the Caribbean or the American colonies. On his first voyage he sailed up and down the coast of West Africa and took 218 slaves to Charleston, South Carolina. Sixty-two Africans died on the voyage, a higher than average loss. We know the details from the ship’s log (now in the National Maritime Museum), not from Newton’s autobiography. He was preoccupied with his own spiritual state and did not seem to notice the sufferings of the slaves.On 11 August 1750 Newton, now a captain, sailed his ramshackle ship, the Duke of Argyle, out of Liverpool. Both the crew and the slaves fell sick. They were back in Liverpool in October 1752 and Newton had a bonus of £257. On his next voyage, in the African, in 1752 he reported on 11 December:

‘By the favour of Divine Providence made a timely discovery to day that the slaves were forming a plot for an insurrection. Surprized 2 of them attempting to get off their irons and upon farther search in their rooms upon the information of three of the boys, found some knives, stones, shot etc and a cold chisel. … Put the boys in irons and slightly in the thumbscrew to urge them to a full confession’. Quoted James Walvin, The Trader, The Owner, the Slave: Parallel Lives in the Age of Slavery (Vintage, 2008), p. 5

His religious convictions deepened in this period, but still he saw nothing wrong with slavery.

Curate of Olney

In 1755 he gained a job on land and over the next few years began to seek ordination. Even though he did not have a degree, he was ordained through the patronage of the Evangelical peer, the Earl of Dartmouth, who owned large tracts of land in Buckinghamshire and had the patronage of the living of Olney. In April 1764 Newton was ordained curate of Olney and was appointed priest in June of the same year. In August his Authentic Narrative was published, and made him a national celebrity. He was an accomplished, if somewhat unconventional preacher, and a caring parish priest, and his congregation grew, so that the church had to be extended to cope with the numbers. |

| Olney Vicarage |

His services were unusual for their choral music, and Newton was encouraged to write his own hymns by the arrival of William Cowper in 1767. Cowper was to become one of the most celebrated poets of the eighteenth century, but he was plagued by a depressive illness that had led to his being confined for a while in an asylum at St Albans. You can learn more about Cowper and Newton from a visit to the Cowper and Newton Museum at Olney.

|

| The Olney Hymns Retrieved from the Library of Congress |

In late December 1772 Newton wrote ‘Amazing Grace’, which was first presented to his congregation in January 1773. In 1779 he published the Olney Hymns. In the same year he was offered the parish of St Mary Woolnoth in the City of London, where his celebrity increased.

Abolitionist

His arrival in London coincided with the beginning of the movement for the abolition of the slave trade. In 1774 Wesley had published 'Thoughts Upon Slavery', which swung most Methodists against the trade. In 1785 Newton became spiritual director to the young MP for Yorkshire, William Wilberforce. In 1786 Thomas Clarkson published his Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species. In 1785 the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed, composed mainly of Quakers.In 1788 Newton made the decision to join the campaign, and published his pamphlet, ‘Thoughts on the African Slave Trade’:

‘I am bound in conscience to take shame to myself by a public confession, which, however sincere, comes too late to prevent or repair the misery and mischief to which I have formally been an accessory… I never had a scruple upon this head at the time; nor was such a thought once suggested to me by any friend.’He gave evidence before a Committee of the Privy Council and until his death in 1807 he was an implacable opponent of the slave trade.

Olaudah Equiano

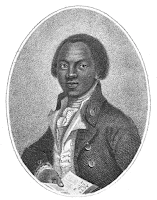

|

| Olaudah Equiano |

In his autobiography, Olaudah Equiano claimed that he was born around 1745 in Igbo in Guinea. However, his baptismal record at St Margaret’s Church, Westminster, dated 9 February 1759, records that he was born in South Carolina, then a British colony. There is therefore some dispute about how autobiographical his account of his early life really was. Was he recounting his own experiences, or distilling the experiences of others who were kidnapped and sold into slavery? For the latest information on this controversy, see here.

Slave

In the summer of 1754 he was sold to a Royal Navy officer called Michael Henry Pascal, who named him Gustavus Vasa, after the sixteenth-century Swedish hero. As Pascal’s slave he served in the navy, and was brought to England in 1754. At sea, he mastered reading and writing and learned about Christianity. He was back in England in 1759 and baptised at St Margaret’s, Westminster.In late 1762 Equiano returned to England, landing at Deptford. He had learned many skills that made him employable, had acquired books, clothes, and money. He believed that because of his baptism he would be free when he arrived in England but instead the captain traded him to another ship bound for the sugar colony of Monserrat, forcing him to abandon his worldly possessions. Whether or not he had been kidnapped in Africa, he was certainly kidnapped now.

In 1763 he was sold to a Quaker, Robert King, who took trained him as a clerk. Though the hours were long his work was less harsh than that of the slaves on the plantations, but his travels on behalf of his master gave him an insight into their sufferings. But within three years he had saved up £40, enough to buy his freedom. He was never to be a slave again.

Seaman

In July 1767 Equiano left Monserrat for England.‘I bade farewell to the sound of the cruel whip and all the other dreadful instruments of torture! Adieu to the offensive sight of the violated chastity of sable females… adieu to oppressions (although to me less severe than to most of my countrymen!).He arrived in London in September, a free man and for the next few months worked as a barber. He learned the French horn and attended evening classes in mathematics. But he was running short of money and he signed on again as a seaman.

In 1773 he became part of a Royal Naval fleet commissioned by the Royal Society and the Admiralty to seek the north-east passage to Asia. The two-vessel convoy was led by Constantine John Phipps, a friend of Joseph Banks. Equiano was on board the Racehorse with the fourteen-year-old Horatio Nelson. The venture was driven back by ice and they had to return after four months. They had sailed further north than anyone before and they had proved that no northern passage to India existed.

Just as Newton discovered faith in a storm at sea, Equiano’s experiences in the Arctic led him to ‘seek the Lord’ on his return. He was most attracted to the Methodists and in December 1774, on his return from another sea voyage, he was admitted to the Methodist chapel in New Way, Westminster. After a further voyage to the Caribbean in 1776 he returned to London and worked as a domestic servant for seven years before making one final voyage.

Campaigner

He returned in 1786 just as the agitation for the abolition of the slave trade was about to get going, and in 1789 he published his two-volume Interesting Narrative as his contribution to the abolition campaign. For the first time he described himself as Olaudah Equiano rather than Gustavus Vasa.Over the next five years he embarked on a series of promotional tours, the first author to do this and he may have made more than £1,000. In 1792 he married the the 31-year old Susanna Cullen from Soham in Cambridgeshire, by whom he had two daughters, though she died in 1796 and his elder daughter the following year. He died on 31 March 1797 and was largely forgotten until historians in the 1960s began to study the history of slavery and the slave trade.

Conclusion

- The Methodist movement became the fastest growing religious movement in the eighteenth century. It was a religion of the heart and attracted converts dissatisfied with existing religion.

- Unlike the Methodists, Anglican Evangelicals remained in their parishes.

- The Evangelical converts, John Newton, William Cowper and Olaudah Equiano became part of the movement for the abolition of the slave trade.

No comments:

Post a Comment